With very few exceptions, meat and poultry processors today will cite labor as the number one challenge in their operations. Although the difficulty acquiring and retaining labor positions in the plant started before the COVID-19 outbreak, the pandemic magnified the problem. Poultry processors use automation in many instances to combat the labor issue, packaging being one of the first and easiest places to start.

“Labor issues started prior to COVID; the virus and its impact made things much worse so the focus on automation has heightened,” said Craig Souser, president and chief executive officer at packaging robotics company, JLS Automation, York, Pa.

JLS’s solutions provide an automated option at every point in the packaging process, from primary product handling to carton loading. However, automation can be a slow process on both ends of the equation. Automation providers and their customers need to practice patience and have a long-term vision.

During the last 10 years the poultry processing industry has been pressured to optimize production efficiency. The ways to do this have often included increasing line speeds, processing heavier chickens, focusing on top yields, working longer hours and keeping downtime to an absolute minimum, said Larry Campbell, vice president of sales, Marel Poultry, North America, Lenexa, Kan. And in addition, processors must maximize sustainability throughout production to satisfy a more demanding consumer base.

“Achieving optimal carcass balance, making the best and most profitable use of each part of the bird and its by-products, has become vitally important for processors in their quest for top efficiency and sustainability,” Campbell said.

Going through changes

Higher yields and lower labor costs represent the bulk of automation’s impact on the poultry processing industry. The major form that automation has taken is the technology of machine intelligence. More electronics-heavy platforms and less reliance on mechanical components provide the ability to fine tune and adjust systems with human-machine interfaces (HMI) rather than hand tools used by people.

“With the introduction of intelligent solutions, such as the deboners with x-ray technology, we now are able to offer customers a higher level of efficient automation and yield improvement, real significant yield improvement and at the same time, with up to half staffing reduction,” said Howard Saul, national accounts manager at Foodmate US Inc., Ball Ground, Ga.

Recently, the processing of dark meat with automation has gained popularity. Whole leg and thigh deboning systems are faster, cut with more precision and are better equipped to handle flock variations. Reaction times for, and the control of, mechanical functions for dark meat cut up are more accurate and produce higher yields than in years past.

“For white meat breast deboning, poultry processors still struggle for the ideal solution to debone big birds automatically,” said Oliver Hahn, CEO, Baader Poultry, USA/Canada, Kansas City, Kan. “The objective is to meet or surpass the benchmark of manual labor with the speeds that automation provides.”

Nevertheless, automation in poultry processing has become a mainstay for all parts of the bird whether cut-up, x-ray, packaging, or any other step in the process.

“Automation has gone from a trend to a necessity and poultry processing manufacturers have been charged to deliver innovative and effective automation solutions,” said Silvana Paterno, marketing communications manager at Foodmate, a subsidiary of Downers Grove, Ill.-based Duravant. “At Foodmate, the introduction to x-ray technology on the deboners has been the most significant development and one that poultry processors were eager to embrace.”

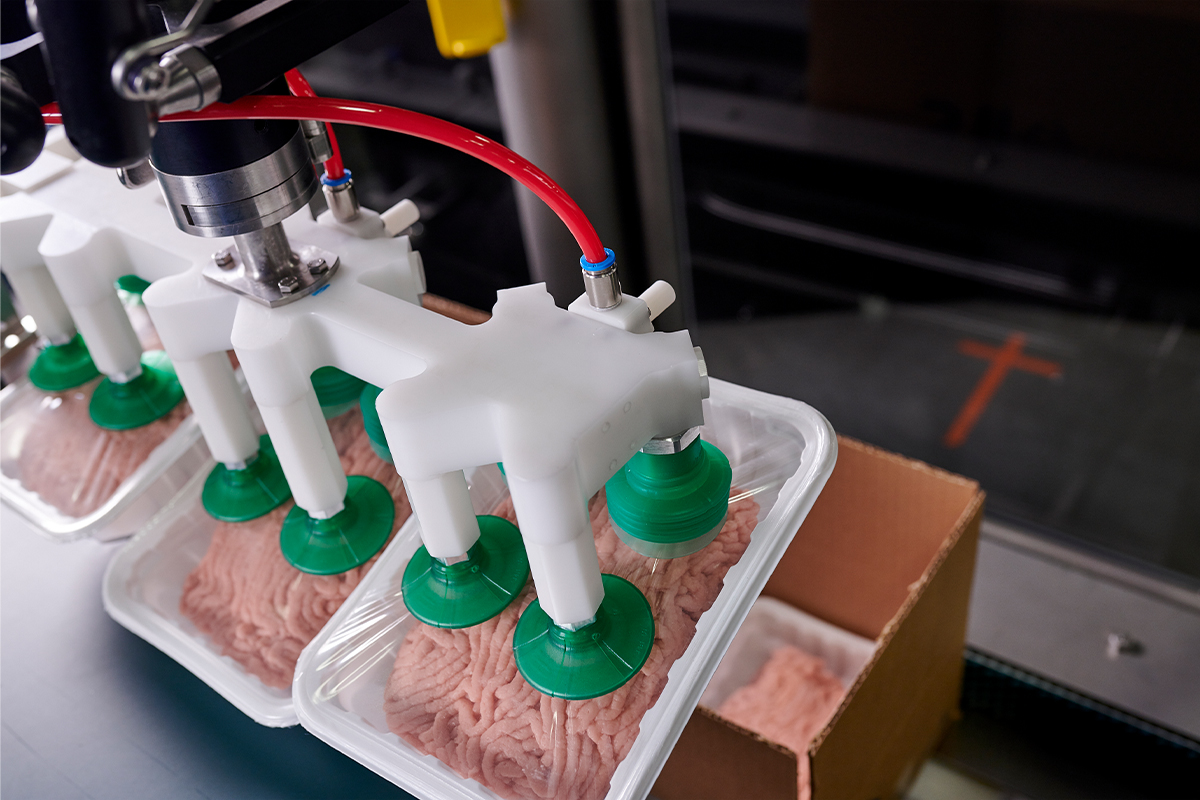

Packaging is a prime starting point to integrate robotics into poultry processing. (Source: JLS Automation)

Packaging is a prime starting point to integrate robotics into poultry processing. (Source: JLS Automation)

Pushing ahead

Automation to a poultry processing line doesn’t necessarily come easy and might not be a quick fix for all processors.

“Lead times are long and costs are high and many of the plants don’t have enough room for automation,” Souser said. “The highest level of savings and largest reduction of labor are often some of the more challenging areas to automate, and again, usually have long lead times. Our focus is on small wins to get started and make sure that the plants can support the technology – walk before you run.”

Automated lines, and their software solutions, perform the most efficiently when set up to run a more precise size and weight range of bird. However, the need for a single processing line to handle a wider size-variety of broilers counters the performance efficiency. One solution from Marel includes weighing before cut-up.

“Cutting portions precisely is the essential hallmark of a truly efficient automatic cut-up system,” Campbell said. “Once again, cutting modules perform best if set to a relatively narrow band of product weights. By weighing all products beforehand, either in the whole product distribution line or in the Marel ACM-NT cut-up system itself, and by doubling up critical cutting modules for ‘light’ and ‘heavy’ products, these can be cut supremely accurately, optimizing yield and quality.”

All poultry processing equipment and technology companies communicate extensively with customers to ensure an ideal situation when building, and before installation of, incoming machinery and software. It’s the communication beforehand that produces optimal results for processors. The level of technology used today necessitates a higher level of service throughout the partnership.

“We support our customers with an experienced service force for installation, training, and production support after the initial installation,” Hahn said. “Today’s automatic solutions are more technically advanced requiring a higher level of maintenance support compared to a manual deboning line. There will always be logistical challenges when changing a process, but our project department works closely with customers to mitigate these issues.”

For a company’s support team specializing in new and cutting-edge technology, the skill transfer to in-house maintenance teams need development and the team members need continuing education directly applicable to the specific automated equipment.

“The newest technology requires a different skill set from the plant staff,” said Adam McCoy, national account manager at Foodmate. “This skill set has never been a part of the ‘standard maintenance team’ requirements. It’s very difficult to find someone who understands programming and mechanical troubleshooting.”

Saul added, “Plants have relied on maintenance technicians with strong mechanical skills and those techs are now being challenged like no other time before. But once the plant has gone through the training we offer, they realize that the systems are actually easier to work on. It’s a mindset that has to be changed at the very start if not before the installation and commissioning. We have training programs and facilitators in place to help through that process.”

Today’s tech

The idea behind automation has always been saving labor, fast(er) line speeds and higher yields with less human error and injury. These remain as the most sought-after advantages and so improving on these concepts further are still the biggest trends. With this comes greater connectivity to the cloud which provides better informed and faster decision making.

“A cloud infrastructure allows processors to receive, store, analyze and share data with greater flexibility and accessibility than traditional alternatives,” Campbell said. “Having data available in the cloud makes it easier to respond to complex issues and make data-driven decisions near real-time.”

According to Hahn, Baader consistently innovates and explores new ideas focused on achieving the highest yields with the least amount of labor. “We employ intelligent automation that captures data for each bird to determine the best route within the cut-up line to maximize production efficiency.”

Automation continues to evolve and take on new forms making it stronger and more useful in new ways. Robotics are already beginning to replace the human hands of manual laborers while x-ray and vision systems see better and are more discerning and accurate than the human eye.

“Currently the use of vision and x-ray technology for increased cutting accuracy is at the forefront of the industry,” said Tracy Allen, product manager for Foodmate. “Moving forward combining robotics with this technology to further increase yields and reduce labor costs will be invaluable.”

Similar to biological evolution, today’s automation and those who work on it, are able to adapt to the environment. The machines take on qualities that allow for survival and perseverance in that environment and develop new abilities accordingly.

“Artificial intelligence and machine learning are moving into the space, especially into vision, opening up applications like bin picking that were not feasible previously,” Souser said.

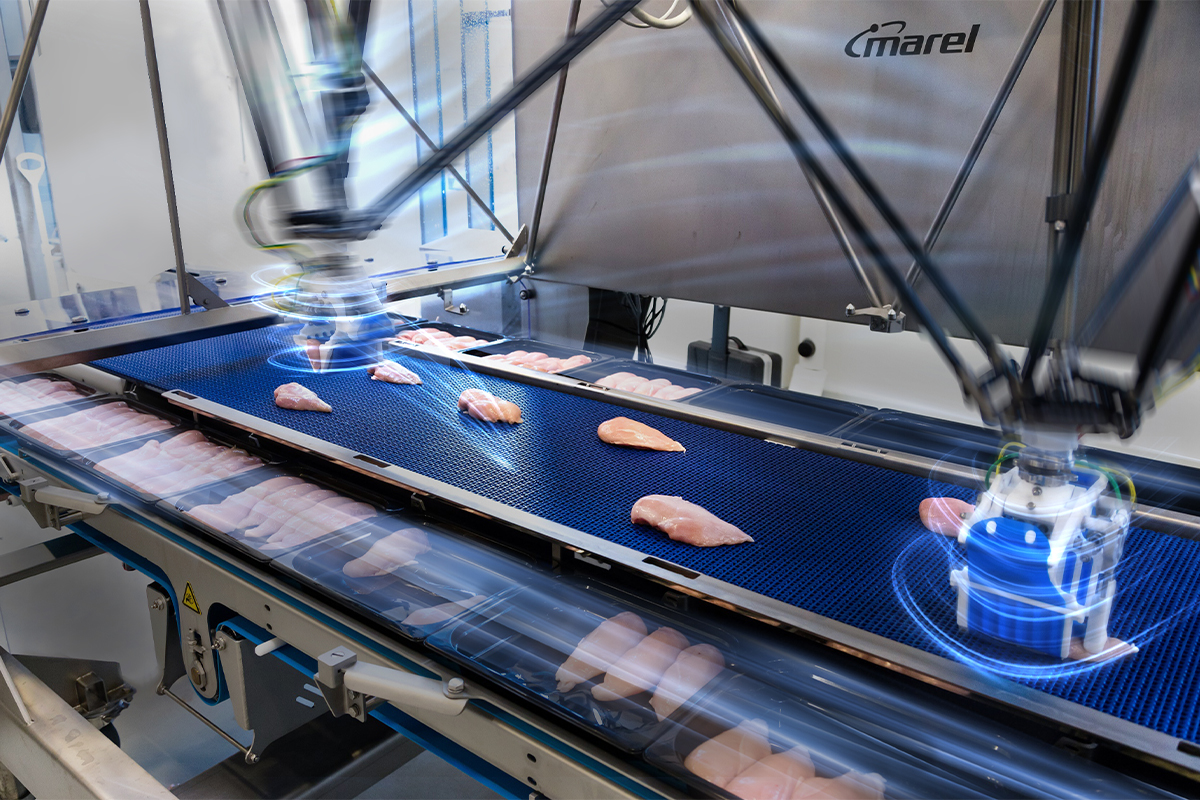

Robotics could eventually replace all human hands in poultry processing in the future. (Source: Marel)

Robotics could eventually replace all human hands in poultry processing in the future. (Source: Marel)

The future

Automation in poultry processing is, and always has been, focused on reducing manual labor and increasing yields at a faster pace. Those in the industry believe that eventually operations will be fully automated, robotized and connected. Human involvement will consist of only supervision and management of automation.

Along with faster speeds, higher yields and cost cutting through less “hand” lines, durability and performance of existing technologies will need to expand into new innovations and technologies. A higher form of AI, machines that learn more and see more at faster speeds, all integrated into the cut-up line with trained people to operate the technology and provide greater flexibility and control with higher quality and increased throughput will be the focus of suppliers in the future.

“Automation is a given, so finding ways to make it work has to be a focus,” Souser said. “We are focused on making the experience sustainable and positive for the future, not something that worked well for a year or two and then became an anchor.”